critique, wordplay, and the digital afterlife of french philosophy

project overview

Context: “Philosophy Twitter”, where participants discuss 20th Century French philosophy.

Objectives:

1. Understanding how and why a less hierarchical, decentralized model of discussion on social media creates open communication yet encourages misconceptions.

2. Analyzing the creativity of these misconceptions.

2. Comparing accessibility requirements for on- and offline discussion groups.

Role: Researcher

Duration: 2.5 years

Methods and Tools: Python/Jupyter Notebooks to query Twitter data, Network Analysis with Gephi, Topic Modelling with Mallet, Sentiment Analysis with VADER, Voyant Tools, distant reading, close-reading, symptomatic reading, interviews, contextual inquiries.

opportunities

Philosophers like Gilles Deleuze and Slavoj Žižek have referred to the history of philosophy as a series of productive misreadings. These exchanges take place equally in philosophical texts and open forums for debate.

When I was working at the UC Paris Center in 2019, I observed that the French have a particularly strong culture of publicly accessible intellectual debate in museums, movie theaters, and seminar-style meetings.

An excerpt from a text by French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan.

problem

I became interested in understanding how the endless exchange of ideas on social media, specifically on “Philosophy Twitter”, might invoke or alter the history of productive misreadings. What are the differences between how on- and offline participants engage in these debates?

Online networks create greater opportunities for open communication and a decentralized model of learning, but social media and blogs also reduce the complexity of dense material and are not well-regulated. Hypothetically, social media creates the conditions for unbridled creative output, but what happens when misconceptions arise that aren’t productive?

the case of french philosophy

As intellectual historian François Cusset observed, 20th-century French philosophy, known for its distinctive vocabulary and concepts, particularly lends itself to “the development of insiders’ codes and playful reappropriation”.

The problem with the constant perpetuation and reuse of jargon within academic circles became especially clear with the discovery of academic hoaxes. The Sokal hoax, for example, exposed peer-reviewed journals that accept essays containing popular, poorly understood catchwords combined with unsubstantiated arguments.[1]

[1] In 2015, the French journal Sociétés was exposed for publishing an article about a “transgender” car-rental service that exemplified the modern episteme. Likewise, the “Grievance Studies” affair in 2017-18 attempted to raise awareness of the weaknesses of postmodernist and identity-based scholarship.

questions

How does late 20th-century French political philosophy resurface on social media, often by way of Anglo-American scholarship?

Which concepts are more or less popular and how does that affect how those concepts are commonly understood?

What kinds of misconceptions arise in academic journals (e.g., Sokal Affair and Grievance Studies Affair) vs. in online discussion?

What does this comparison imply for wider debates about viral media and its role in political polarization?

Writer Emily Herring, turns a popular meme format into a pithy comparison of philosopher Henri Bergson’s notions of time.

methods

My methodology is based on the idea that French philosophers are known for their distinctive vocabulary. These “insiders’ codes”, as Cusset calls them, are what create a common vantage point for debate. So I set out to compare the use of key topics and related terminology off- and online.

In Fall 2019, I conducted contextual inquiries and interviews to learn about participant interaction and gain a first-person perspective on philosophical debates at various Parisian museums, movie theaters, and seminar-style meetings, such as Organisation Non-Philosophique Internationale (ONPhI) and L'École de la Cause freudienne (ECF).

Working with the Data Science Center at UCLA in 2020-21, I developed a database of terminology to query on Twitter. The tweets and relevant metadata I gathered were analyzed using three main methods[1]:

a. Topic modeling, sentiment analysis, and network analysis that presented broader trends in the data.

b. Literary or textual analysis that provides a close reading of key tweets, corresponding to their use in primary texts.

I combined quantitative and qualitative methods of content analysis to look for popular topics in tweets and their relevance to contemporary issues in adjacent fields like art, literature, and politics. Then I honed in on topics or concepts with more volume and variety of data to see how participants were discussing the most active and diverse debates. I also paid particular attention to any topics with high polarity scores and analyzed any tweets suspected to contain bias through close-reading methods. Network graphs of tweets, replies, and retweets allowed me to visualize the connections within conversations related to a particular terminology or concept.

[1] This research project, including the close reading I performed on individual tweets, is based on a limited set of data that was queried using Twitter’s academic API key. As a researcher, it was not possible to verify the precise parameters of my search results.

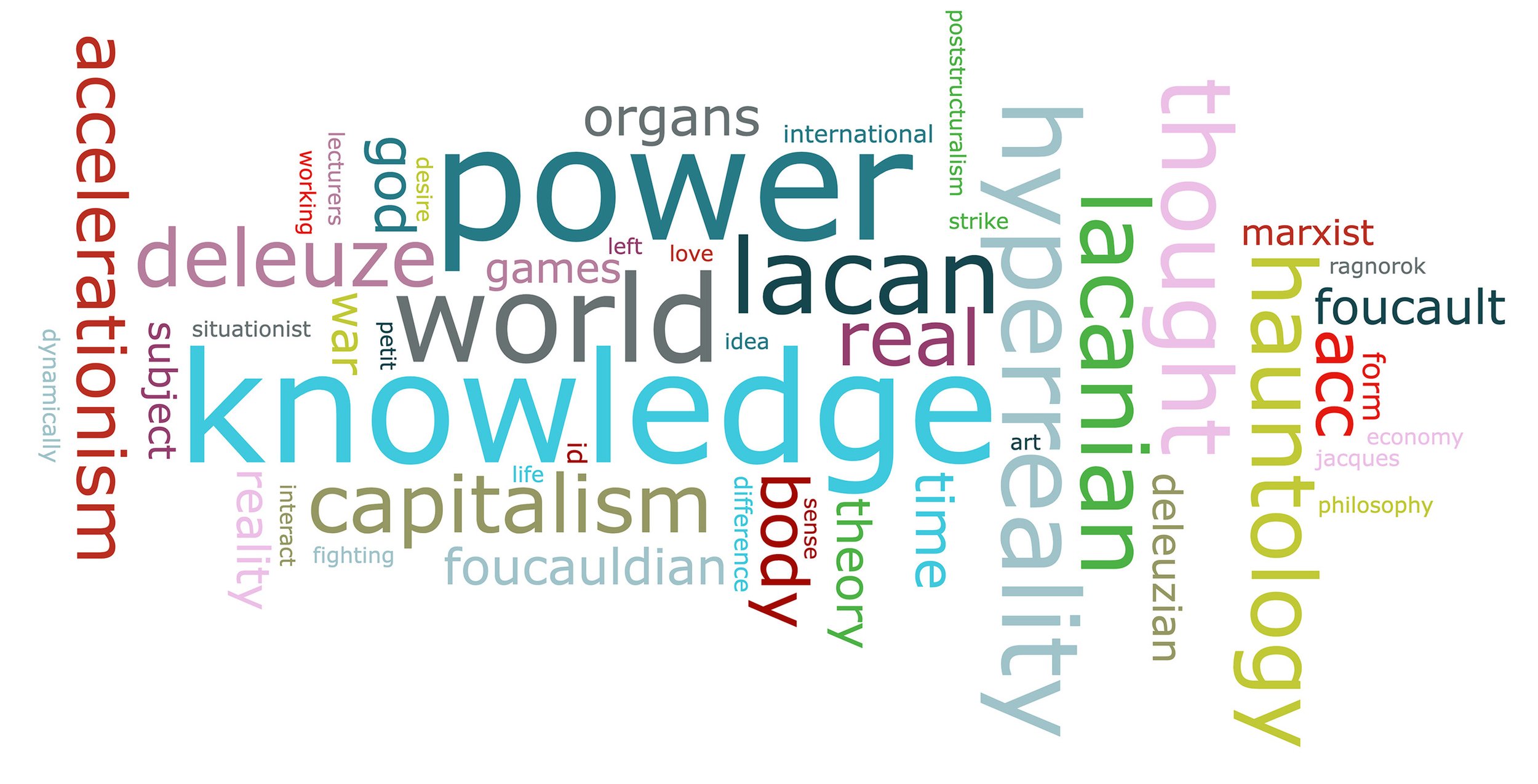

word cloud of top words from english language tweets

Tweets from October-December 2021

network graph of tweets, retweets, and replies

Visualization of tweets from October-December 2021 made with Gephi showing 11,327 tweets as nodes, 9,614 retweets and replies as edges.

findings and implications

“Philosophy Twitter” takes up many of the same debates that are prominent in academic discourse, while also posing new questions that reread classic French texts in the context of contemporary social and political issues. However, Twitter abounds in improper citation and jargon. And while shared vocabularies do drive debate, they also foster gatekeeping and shut down public debate.

The instances of misconception or disinformation, I found, aren’t generally any worse on social media than in academic publishing. “Philosophy Twitter” demonstrates the importance of common referents to the integrity of an online community yet suggests that those referents can actually prevent diversity and innovation.

Increasing the number of possibilities for knowledge exchange without any well-defined limits does not produce innovation. Rather, there can be no innovation or diversity if there’s endless innovation or diversity.

The quilting point is an example of unique and oft-quoted terminology used by French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan.

implications for social media

This research is widely relevant to mitigating mis/disinformation on social media. As my research demonstrates, shared vocabularies foster accessibility. But when a concept “goes viral”, the likelihood of misconception increases. Unlike classrooms, digital platforms are unmoderated, which can lead to erroneous arguments or sharing of unverified information. This creates an atmosphere of mistrust. The challenge for social media research in an array of disciplines is to expand accessibility and diversity while discovering principles or features that will help develop trust and safety in online forums.

impact

Though this project was never officially completed, I had the opportunity to test the concept of my research by designing and teaching a class called “Social Media and Storytelling” at UCLA in the Summer of 2020. The objective of this class was to understand the history of digital storytelling by comparing classic texts about philosophy and literary criticism with social media narratives.

Through their writing and creative projects, my students, mostly juniors and seniors, demonstrated their skills in internet literacy, critical thinking, and evidence collection. They also showed me they could implement basic text-mining strategies and design visuals and text to convey what they had learned. I end this case study with a few highlights from my students’ writing.